Key Takeaways

- The NYT article gets a few things right—NAD confusion in the market, the need for more large-scale human trials, and the lack of evidence behind IV infusions.

- The article also misses critical context, including the fact that there are already dozens of human studies demonstrating measurable NAD increases and related health benefits.

- It blurs the line between IV therapy and oral precursors. These are very different approaches and only the latter has meaningful scientific support.

- It leans heavily on cautious voices without balance. Pioneers like Dr. David Sinclair and Dr. Andrew Salzman, who’ve published extensively on NAD biology, were notably absent.

- NAD’s importance isn’t in question—the focus should now be on how to best support it safely and effectively over time.

We love reading hot takes on the ever-growing longevity space, especially when it’s related to NAD. And when an esteemed publication like The New York Times covers the topic, well, the world listens. Public interest in NAD and precursors like NMN and NR have skyrocketed, and journalists are nicely positioned to help readers navigate the fast-moving field. But we’ll be honest—we read the Times’ “Longevity Seekers Are Taking NAD+ Supplements. Do They Work?” (warning: paywall) with growing dismay. While the piece does raise a couple of legitimate concerns, it leaves out a lot of critical context that paints a far more accurate picture of where the science stands today. So in the interest of an informed scientific discussion, we’re breaking down what the article got right, what it missed, and how readers can better understand the real state of NAD+ research.

What the New York Times got right

The Times article has a few valid points that align with what many researchers and responsible brands already acknowledge. Let’s give credit where it’s due before we cover all the ways the piece goes sideways.

It points out legitimate industry confusion

The article calls out the fact that the NAD landscape can be pretty darn confusing. Between the spas hawking NAD IVs promising “instant rejuvenation” and more supplements brands than you can count, it’s easy to wonder what’s real and what’s just marketing. Worse, there’s a ton of variables from brand to brand, and that includes dosage, quality, even plain old terminology—we’ve seen “NAD,” “NAD+,” “NMN,” and “NR” used casually and even interchangeably, when they really shouldn’t be.

Adding to the confusion are companies making claims about raising NAD levels with ingredients that either haven’t been shown to do so or are simply less effective. Some brands sell straight NAD (which the body doesn’t absorb efficiently), while others lean on weaker precursors like niacin and still promise the same cellular benefits.

It’s natural that all of this confusion creates skepticism, and any article asking readers to think about peer-reviewed evidence and transparent sourcing has our respect. But we’ll take it a step further—that clarity should also include how the data is presented.

It highlights the need for stronger human data

We talk about this a lot, and we aren’t the only ones in the longevity space doing so. NAD research has grown tremendously in the past decade, but it’s still an evolving field. Large, long-term human trials are absolutely essential for establishing not only short-term biomarker changes but meaningful outcomes tied to aging, resilience, and disease prevention.

On the other hand, it’s inaccurate—and misleading!—to suggest the data isn’t there at all. The Times article overlooked the 95 human studies on NAD and 12 human studies on NMN already published in PubMed alone. These include multiple randomized controlled trials demonstrating significant increases in blood NAD levels, improved insulin sensitivity, and enhanced mitochondrial function—all in humans. That’s not to say we don’t need more research, but it’s certainly a more balanced depiction of the current science.

It questions NAD IV therapy (and that’s fair!)

This is perhaps the strongest part of the article. NAD IV therapy has become a wellness trend practically overnight, often with bold claims that outpace the evidence. The problem? Very few controlled studies exist on intravenous NAD, and dosing protocols vary wildly between clinics. For a molecule as metabolically active as NAD, delivery method matters, and scientific evidence for IV therapy is still limited at this point.

Oral NAD precursors like NMN and NR, meanwhile, have undergone extensive study. They’re proven to raise NAD levels safely and consistently through well-understood metabolic pathways. It’s important for consumers—and journalists, if we may be so bold—to recognize that the scientific promise lies in these precursors, not in unregulated IV infusions.

At Wonderfeel, we focus on what’s been validated in controlled settings: bioavailable, orally delivered NAD precursors supported by human trials. That distinction is key to separating true longevity science from wellness marketing.

Where the article falls short

The big issue with the Times piece isn’t the questions it’s posing—it’s the serious lack of context in the answers. In other words, the strengths in this story also set up its weaknesses.

There’s already a meaningful body of human research

We already mentioned the dozens and dozens of human clinical trials into NAD and NMN on PubMed, which hardly qualifies as a research void. These include randomized, placebo-controlled trials showing measurable, reproducible increases in NAD+ levels in blood and tissue, along with improvements in insulin sensitivity, mitochondrial function, and even vascular health in older adults. By failing to acknowledge this extensive body of work, the article leaves readers with an incomplete understanding of the field’s progress. Worse, it suggests that NAD science is speculative when that really isn’t the case.

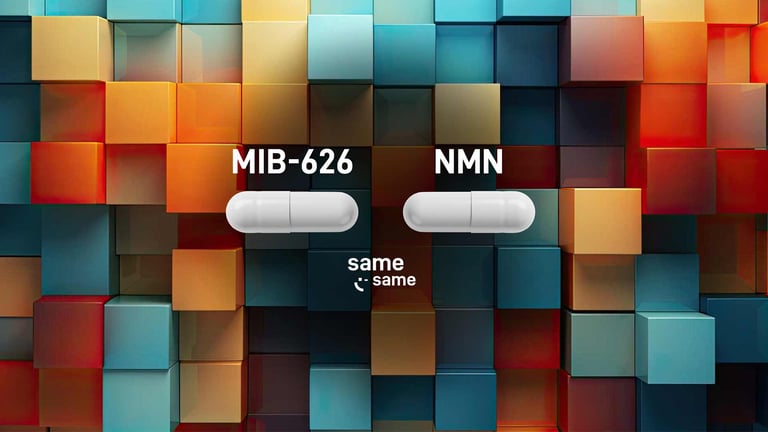

It conflates NAD IV therapy with NAD precursors

IV infusions and oral NAD precursors aren’t interchangeable. IV delivery lacks robust peer-reviewed validation, while NMN and NR have undergone numerous controlled human trials with consistent results. Oral precursors are metabolized naturally in the body and raise NAD levels through well-established pathways without the variability (and needles!) of IV therapy. To lump them all in together does readers a disservice because it blurs the line between scientifically validated supplementation and unregulated clinical procedures. But it’s a really important distinction, because the science is advancing through rigor—not hype.

It quotes skeptics—and largely overlooks pioneers

The Times does feature a mix of solid academics and respected scientists, including Dr. Shin-ichiro Imai, Dr. Eduardo Chini and Dr. Joseph Baur, many of whom have advanced important questions about NAD biology. Their cautious takes are important, but the framing of the article focuses almost entirely on the reservations and not their contributions.

Case in point? Dr. Imai is quoted to illustrate scientific caution without acknowledging the significance of his research showing clear, measurable NAD benefits in both animal and human studies. It’s an omission that subtly shifts the narrative from science in progress to science in doubt.

A more balanced story would have also included pioneers like Dr. David Sinclair and Dr. Andrew Salzman, whose decades of published research in NAD biology provide essential context for interpreting today’s findings. As it’s written, the piece underrepresents the scientific depth of the field and overstates the uncertainty.

What the science really shows

Here’s what we actually know about NAD and its precursors right now.

- NAD declines naturally with age. This isn’t controversial—decades of research confirm it. That decline is linked to reduced cellular energy, slower DNA repair, and an increasing vulnerability to metabolic and neurodegenerative conditions.

- Raising NAD levels is measurable and reproducible. Multiple human studies have shown that supplementation with NAD precursors like NMN and NR can increase NAD levels, improve muscle insulin sensitivity, and support mitochondrial function.

- Safety profiles are strong. Across dozens of clinical trials, oral NAD precursors have demonstrated excellent tolerability, with few mild side effects reported.

NAD isn’t a mystery molecule—it’s one of the best-characterized players in cellular metabolism. The question isn’t if it matters, but how we can best support it over time.

That’s what makes the Times piece so frustrating. Instead of exploring this deeper question—the “how”—it gets stuck debating the “if.” But the science has already answered that part! The real conversation should be about translating decades of cellular and clinical research into responsible, accessible ways to help people live longer, healthier lives. It’s what we’re doing right here at Wonderfeel.

The bottom line: Why balance matters

The Times piece raises fair questions. But we wrote this response because we believe readers deserve more complete answers—ones that reflect both the rigor of ongoing studies and the measurable advances already made. At Wonderfeel, our goal isn’t to hype—it’s to clarify. And it’s pretty simple, really. When the conversation around longevity stays balanced, everyone benefits.